FROZEN: The Post-pandemic Real-Estate Crisis By Evan Anderson _____ Why Read: Real estate has long been one of the safest asset classes. Residential homes have also been one of the most important stores of wealth for the average American family. All of this is beginning to change. Read on for a description of how and why the US real-estate market, from residential to commercial, has frozen, and what else is contributing to the new, uncertain future in which the industry now finds itself. _____ Real estate cannot be lost or stolen, nor can it be carried away. Purchased with common sense, paid for in full, and managed with reasonable care, it is about the safest investment in the world. - Franklin D. Roosevelt Landlords grow rich in their sleep. - John Stuart Mill Buy land; they're not making it anymore. - Mark Twain

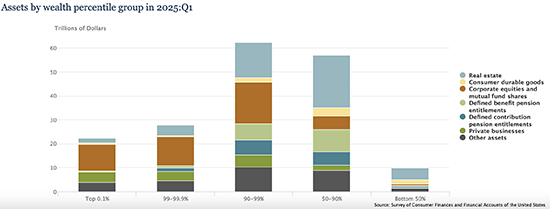

In the early days of the 2008 Global Financial Collapse (GFC), a notable aspect of the housing-market crash was the sheer quantity of liquidity flying around the room. Banks were issuing loan deals that could best be described as "unhinged," then packaging them as fast as possible to resell and move off their books. The results were predictable: plentiful, effectively fraudulent NINJA ("no income, no job, no assets") loans that were never going to survive the life of the term, leading to massive and sudden surges in non-performing packages. Some of the collapsing banks had invested at the top of the system, with no clear tracking of who had been responsible for ensuring that packages did not contain such "poison pills." If anything, the experience of the 2008 financial crisis solidly challenged the kinds of exuberant philosophies quoted above: those men of yore lived in an economic and financial system far less defined by such financial product hijinks. The backlash from the GFC was, rather predictably, massive bailouts paid for by the public and a series of regulatory changes that attempted to prevent the same from occurring in the future. The pendulum had swung. Today, against the backdrop of a global pandemic that shocked all markets in various ways, and a huge amount of government spending in response under our belts, we sit on the precipice of a different kind of crisis. The housing market, rather than overheating, is beginning to freeze. What does a frozen market look like? In comparison to free money flowing everywhere, we now see an emerging dynamic that is as perturbing as that of 2008: prices are sky-high, demand is dropping fast, and interest rates are holding steady at a near 7% level. In today's US housing market, it's beginning to feel as if the adage about work -"No one wants to buy houses anymore" - is playing out. Rather than moving on with a shrug, however, we should be paying close attention. The main problem? In 2023 (the latest year we have numbers for from FRED), NAICS code 531 ("Real Estate") was worth almost US$3.45 trillion. That's roughly 12.45% of that year's US GDP. In other words, in macroeconomic terms, real estate matters. More important, it remains one of the largest stores of American wealth, particularly for the middle and upper classes. As the above chart shows, real estate represents the largest share of wealth for the bottom 50%, but also for the 50%-90% of wealth holders. It is highly relevant in the 90%-99% group, along with equities - and tapers only at the top, where equities dominate. All of this means that for both housing and financial security, a significant proportion of the nation depends on the housing and real-estate markets functioning smoothly in order to be "wealthy." But that isn't what's happening.

With home sales sluggish, and home building and house prices poised to plummet too, Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody's Analytics (MCO), says he's sending up a "red flare" about the state of the housing market. "Housing will ... soon be a full-blown headwind to broader economic growth," he wrote in a post on X and LinkedIn, "adding to the growing list of reasons to be worried about the economy's prospects later this year and early next." - MorningStar (7/15/25)

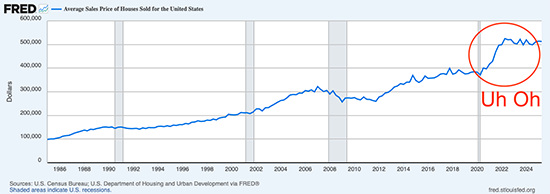

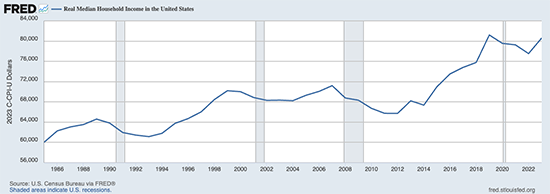

Starting in 2020, flows of pandemic-era fiscal stimulus began to hit the residential-housing market. With wealthier families seeking to move out of urban areas to find the perfect hideout, more cash in the market on all sides, and inflation across all categories rising fast, the cost of residential housing blew up. But while stimulus through various programs was putting more cash in the pockets of investors and business owners, and mortgage rates were near-zero, average incomes were simultaneously going down. Thus, when housing prices were rising faster than at any other time in modern history, and the borrowing costs were gone, the ability of those buying to actually pay for a house dropped over time. The results were predictable: people with flat incomes bought houses at low rates quickly, and prices skyrocketed, with one caveat: many would not be able to move or to afford a new mortgage at a higher rate. This is now slowly beginning to resolve (see the increase in incomes at the far right in the chart above), but hardly enough to keep up with the price increases that near-zero-rate mortgages created. In all, average all-market price growth from 2000-24 was somewhere around 60%, while median incomes grew closer to 19% in the same period. The problem is clear. For the housing market to return to a healthier state, one or more factors need to change: incomes could rise, prices could fall, or interest rates could go back to near-zero. Splitting the difference (incomes rise, prices fall, and rates go down) could get the market to a place again where households can afford to buy, but it would take a lot to erase the 40% additional gain (effectively, price inflation) that has outpaced family incomes. With jobs numbers currently faltering in the US, the consensus is that the Fed may choose to drop rates this fall. But dropping rates can only go so far. Some combination of factors needs to happen before the housing market gets real life breathed back into it. The data makes this even clearer. The median income of an American household in 2024 was $86,000. Traditional wisdom would hold that the average American household should spend no more than 30% - or $2,150 a month - on housing. Current mortgage rates (~6.7%) at the median house price ($410,000) would be somewhere around $2,500, and the mean house price is closer to $510,000. For reference, a house priced "affordably" for the average family would cost more like $380,000 with a 4.71% interest rate. So, American families are either overpaying (and suffering in their savings rates or daily lives) or are simply unable to purchase across wide swaths of the market. This is showing up now in other data. According to Realtor.com (emphases in the original):

So, too, have developers noticed the issue. While in many regions one way to deal with the affordability crisis would be to add units, builders are not eager to do so in this environment. New housing starts are down from last year - a fact perhaps unsurprising, given the fact that building costs are on the rise and homes aren't moving. In fact, the US hit a record gap between buyers and sellers, according to a May 2025 report by Redfin, with 500,000 more people trying to sell a house than to buy one. If the houses aren't moving, developers aren't building, and the prices aren't dropping, the market is frozen.

A lot of real estate isn't so good any more. [...] We have a lot of troubled office buildings, a lot of troubled shopping centers, a lot of troubled other properties. There's a lot of agony out there. [...] Every bank in the country is way tighter on real estate loans today than they were six months ago. [...] They all seem too much trouble." - Charlie Munger, then-Vice Chair of Berkshire Hathaway, quoted in the Financial Times (4/30/23)

If the housing market is freezing up, then how about the commercial sector? Weakness here is slightly less formidable, with noticeable improvement in price growth since the brutal days of the early pandemic, which emptied corporate offices and slowed or even stopped factory and industrial work. But rising uncertainty has begun to slow transactions in the commercial sector, as well. According to a report by Altus, the situation across much of the commercial sector appeared to be similar going into 2025. Prices have risen slightly, but transaction activity is down: The first quarter of 2025 was a moody one, as eager anticipation turned to angst ahead of the tariff-driven trade turmoil that was majorly felt in early April. While CRE [commercial real estate] was generally less exposed to broader market volatility than other asset classes, it was not immune. As expectations for overall real economic growth declined through the quarter, uncertainty increased, delaying decisions throughout the CRE ecosystem from individual leasing and transaction decisions at the individual property level to the Fed's next interest rate cut. Amidst the challenging backdrop, single property transaction activity across the traditional CRE property sectors (industrial, multifamily, office, retail, hospitality, commercial general) remained low. However, despite the deteriorating macro environment, the CRE market continued to function, and there were some signs of positivity. For example, the property sector that everybody loves to hate, office, showed signs of improvement in terms of total dollar volume and average size of properties transacted. It must be said that when it comes to descriptions of the health of an industry (or not, as it were), statements like "despite the deteriorating macro environment, the CRE market continued to function" are more than troubling. Commercial real estate was, of course, badly harmed by the absolute bombshell of the pandemic. It isn't easy to recover from the kinds of lows seen in a near-halt of economic activity involving commercial buildings. Even so, five years down the road, one might hope to see a rosier picture in the market than this. So, as in housing - but slightly less so - commercial is seeing some limited price growth, low demand, and little incentive to build.

Meteorologists see perfect in strange things, and the meshing of three completely independent weather systems to form a hundred-year event is one of them. - Sebastian Junger, The Perfect Storm

If the meteorological qualities that created the "perfect storm" described by Sebastian Junger were trifold, the aspects currently on view in the real-estate market could be labeled "more perfect." Interest rates, income levels, and inventory all have their role to play, to be sure; but so, too, do other gathering clouds indicate a more complicated problem. What else lies on the horizon is troubling, at the least. Let's consider some additional factors at play in the freezing of real-estate markets we see coming down the line:

The rise of private-equity and other large investment groups, as well as medium and mom-and-pop investors in residential housing, creates less elasticity in the market. These groups - particularly the larger ones - can afford to sit on real estate and try to keep prices high, by comparison to families that go bust quickly when overextended. As reported by Scotsman Guide: The trend of investors buying single-family homes has become more prominent since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and has also garnered a lot of debate. The share of investor purchases of single-family homes averaged about 17% in 2019, according to a recent CoreLogic report. The share jumped during the pandemic and has averaged 28% since. While the share remains elevated, the number of single-family purchases by investors did slow from the pandemic peaks as overall home sales have slowed in 2023 and 2024. Still, investors currently purchase about 90,000 homes per month on average, down from about 120,000 homes purchased during the 2022 peak. Ninety thousand homes per month is rather a lot. Given that the total number of active listings is sitting just above 1 million, an annual demand from investors that matches nearly the entirety of listings that year is noteworthy.

While the total effects of tariffs (and the tariff schedules themselves) remain to be worked out, many of the planned tariffs today will have a significant effect on builders and final prices. Canadian lumber has long been a major input to the US building industry, across the spectrum. Cheap Canadian lumber has, in effect, subsidized construction in the US due to free-trade agreements; it just wasn't largely discussed. The US does not have enough timber available to match anywhere near the demand that was supplied by Canada - so, with new tariffs, prices will rise steadily. This August 5 report by the National Association of Homebuilders offers a relatively plain view of the effects. But imagine the same for plumbing, electrical, steel, roofing, and all the other inputs to production. Even if the United States reshores most of this, prices will rise. And reshoring, if and where possible, will take years.

Anyone who has been on a job site in the United States is aware that a significant proportion of construction workers are immigrants. Legal avenues for immigration are limited for construction; Immigration Forum estimates that nearly one-fourth of those in the US construction workforce are undocumented. Replacing even those undocumented workers, if deportations continue at their current pace, will be a long-term challenge - not to mention the challenge of improving legal avenues for immigrants at a time when legal immigration appears set to slow dramatically. Allianz projects that US legal immigration will slow by 50% by 2026. If this is anywhere near true - and it appears that it will be - the industry will be hard-pressed to build as it is, much less increase housing and project starts if desired.

We are entering an era in which housing units are being destroyed at a record pace, and destroyed units are not always replaceable. So far, the destruction from climate-change effects comes mainly in the form of massive lost infrastructure and housing, rather than lives - although that, too, is changing. According to numbers from Climate.gov for the year 2024: In 2024, there were 27 individual weather and climate disasters with at least $1 billion in damages, trailing only the record-setting 28 events analyzed in 2023. These disasters caused at least 568 direct or indirect fatalities, which is the eighth-highest for these billion-dollar disasters over the last 45 years (1980-2024). The cost was approximately $182.7 billion. While accurate statistics will likely not be available from here on out, the number of disasters that have already occurred in 2025 appears to rival those mentioned above, and this is just the beginning. The obvious tangential consequence - which we reported on in "SNS: The End of Insurance" (2/12/20) - is that insurers can no longer afford to cover many houses. This played out brutally during last winter's wildfires in Los Angeles, and it continues apace. Uninsurable houses, particularly in vulnerable areas, will likely become valueless.

As with the labor market, broader demographic shifts will surely play deeply into the dynamics of the housing and commercial real-estate markets. While the Baby Boomer generation currently holds a disproportionate percentage of American housing - and is expected to add up to 9.2 million homes to the market by 2035 - rising life expectancy and the fact that 54% of Boomer poll respondents checked that they do not intend to ever sell their homes put those numbers for added stock on the market into question. It remains to be seen how the market dynamics of an aging generation rich in housing units will meet reduced in-migration and the smaller generations below it that have historically reduced buying power.

To make matters worse, the cost of owning a building is dramatically increasing. From HVAC installation to regular maintenance, nearly every aspect of holding and maintaining a building is becoming unsustainably expensive. An October 2024 report from Thumbtack, which indexes home maintenance costs, found those costs to average $10,147 a year - up 4.69% year over year (again outpacing average income growth). This will only be compounded by the other factors on this list.

Between the rising use of AI, the already-slow pace of income growth, and the newly steep downward revisions in jobs numbers the US administration tried to "fix" early this month, it's far from clear that the employment situation is at all stable. For the housing market to begin to move again, there needs to be strength in the labor market, since someone will need to be buying.

As a capstone, the US continues to face elevated inflation. A problem that can be dealt with traditionally by Fed policy keeping rates higher is now at interplay with administration pressure and slowing job-growth numbers, as highlighted by last week's threatening of Jerome Powell with investigation. A bigger problem, however, is that CPI is now at 2.7% and growing again (likely due to tariffs) - meaning, it isn't where we want it to be. If jobs numbers continue to weaken, the Fed will have to choose between one of two bad options: lower rates in an attempt to boost jobs numbers and economic activity and worsen the inflation issues, or its opposite. Neither option is rosy, but rising interest rates could quickly catch up with any additional buying power in the housing market afforded by lower rates. This is not a simple issue; another explosion in price inflation could worsen demand for housing further rather than boost "buyability" in the medium to long term.

It's not a good idea. It's not a good idea because real estate is more interest rate sensitive than it is even inflation sensitive so if you were to say: "If this environment happens does it go ... it goes down in real terms." It's also an asset that is a fixed asset that is the easiest asset to tax. - Bridgewater Capital founder Ray Dalio, responding to a question about whether real estate is a good investment (6/26/25)

Whatever decisions are made by the actors at play in the next few months - and years - the real-estate market has a problem. Cost of building will almost certainly continue to go up, prices are unsustainably high and slowly continuing to rise, and Fed policy alone will not likely fix the issues. Meanwhile, other troubling trends continue to arise that only serve to exacerbate the ailing markets. The age-old wisdom that owning real estate is always a winning proposition may finally be in jeopardy. The market is freezing; responses to that freezing will have their own ramifications. Without an improvement in many of the factors described above, it is hard to picture the markets becoming less stuck anytime soon beyond localized, small improvements. The implication is that real estate has become drastically more questionable as an investment, on both commercial and residential fronts. Readers should beware the minefield of downside risks. Whether in residential or commercial, returns on investment are getting hammered. They simply cannot continue to hit the levels they have in the past few decades. At least, not without big, big changes. As per the quotes at the beginning of this piece, all of these factors strongly challenge the traditional idea that real estate will always be a high-performing investment. That doesn't appear to be the world we live in any longer. This, of course, begs a broader question about our new and strange economic times: If real estate isn't safe, then what is?

[Note: As this piece was going to press, US Producer Price Index numbers were released showing a 0.9% jump in prices from June, with a total of 3.3% for the year - an indication of worsening inflation.]

Your comments are always welcome.

Sincerely, Evan Anderson DISCLAIMER: NOT INVESTMENT ADVICE Information and material presented in the SNS Global Report should not be construed as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained in this publication constitutes a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer by Strategic News Service or any third-party service provider to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments. This publication is not intended to be a solicitation, offering, or recommendation of any security, commodity, derivative, investment management service, or advisory service and is not commodity trading advice. Strategic News Service does not represent that the securities, products, or services discussed in this publication are suitable or appropriate for any or all investors. We encourage you to forward your favorite issues of SNS to a friend(s) or colleague(s) 1 time per recipient, provided that you cc info@strategicnewsservice.com and that sharing does not result in the publication of the SNS Global Report or its contents in any form except as provided in the SNS Terms of Service (linked below). To arrange for a speech or consultation by Mark Anderson on subjects in technology and economics, or to schedule a strategic review of your company, email mark@stratnews.com. For inquiries about Partnership or Sponsorship Opportunities and/or SNS Events, please contact Berit Anderson, SNS COO, at berit@stratnews.com.

* Mark will be speaking at, and/or attending, the following conferences and events: * September 3: Pattern Computer Investors' Event, Kirkland, WA. * September 24-25: 11th Founders World Summit, Stockholm. * October 21: AI Summit 2025, Hamburg. * October 30: ThinkEquity Conference, NYC.

Copyright 2025 Strategic News Service LLC "Strategic News Service," "SNS," "Future in Review," "FiRe," "INVNT/IP," and "SNS Project Inkwell" are all registered service marks of Strategic News Service LLC. ISSN 1093-8494 |